This post marks the official opening of the mini-polymath4 project to solve a problem from the 2012 IMO. This time, I have selected Q3, which has an interesting game-theoretic flavour to it.

Problem 3. The liar’s guessing game is a game played between two players

and

. The rules of the game depend on two positive integers

and

which are known to both players.

At the start of the game,

chooses two integers

and

with

. Player

keeps

secret, and truthfully tells

to player

. Player

now tries to obtain information about

by asking player A questions as follows. Each question consists of

specifying an arbitrary set

of positive integers (possibly one specified in a previous question), and asking

whether

belongs to

. Player

may ask as many such questions as he wishes. After each question, player

must immediately answer it with yes or no, but is allowed to lie as many times as she wishes; the only restriction is that, among any

consecutive answers, at least one answer must be truthful.

After

has asked as many questions as he wants, he must specify a set

of at most

positive integers. If

belongs to

, then

wins; otherwise, he loses. Prove that:

- If

, then

can guarantee a win.

- For all sufficiently large

, there exists an integer

such that

cannot guarantee a win.

- All are welcome. Everyone (regardless of mathematical level) is welcome to participate. Even very simple or “obvious” comments, or comments that help clarify a previous observation, can be valuable.

- No spoilers! It is inevitable that solutions to this problem will become available on the internet very shortly. If you are intending to participate in this project, I ask that you refrain from looking up these solutions, and that those of you have already seen a solution to the problem refrain from giving out spoilers, until at least one solution has already been obtained organically from the project.

- Not a race. This is not intended to be a race between individuals; the purpose of the polymath experiment is to solve problems collaboratively rather than individually, by proceeding via a multitude of small observations and steps shared between all participants. If you find yourself tempted to work out the entire problem by yourself in isolation, I would request that you refrain from revealing any solutions you obtain in this manner until after the main project has reached at least one solution on its own.

- Update the wiki. Once the number of comments here becomes too large to easily digest at once, participants are encouraged to work on the wiki page to summarise the progress made so far, to help others get up to speed on the status of the project.

- Metacomments go in the discussion thread. Any non-research discussions regarding the project (e.g. organisational suggestions, or commentary on the current progress) should be made at the discussion thread.

- Be polite and constructive, and make your comments as easy to understand as possible. Bear in mind that the mathematical level and background of participants may vary widely.

Have fun!

[…] just opened the research thread for the mini-polymath4 project over at the polymath blog to collaboratively solve one of the six […]

Pingback by Mini-polymath4 discussion thread « What’s new — July 12, 2012 @ 10:01 pm |

Obvious observations:

It seems for part 1 we have to provide a strategy for B to always win and for part 2 to give a strategy for A to win at least sometime. But it is not clear if A can ALWAYS win in case 2, finding a counter example would be a good first step

Comment by Bob — July 12, 2012 @ 10:11 pm |

The fact that player A has to choose the number N at the beginning of the game is intriguing. The number of possibilities for x is originally N, so it would seem like large N would make the game harder for B. I suspect that B can counteract the difficulty by asking many more questions for large N than small N.

Comment by Mihai Nica — July 12, 2012 @ 10:17 pm |

Are there any results from Ramsey theory or related which might be useful for part one?

Comment by Jaakko — July 12, 2012 @ 10:19 pm |

Obvious: If we choose sets S_p to be of the form “numbers less than N with a 1 in the pth place of their binary expansion,” then we can get at least 1/(k+1) of the binary digits of x by asking about the p’s in turn.

Comment by Jon — July 12, 2012 @ 10:22 pm |

More generally, for any partition of some set of numbers into 2^(k+1) parts, one round of questioning allows to rule out one of the parts.

Comment by Vladimir Nesov — July 12, 2012 @ 10:34 pm |

…hence, while we can partition N into 2^(k+1) non-empty parts, we can rule out something each round of k+1 questions. We can go on ruling out numbers until no more than 2^(k+1) possible answers remain. After that, we need to somehow cut that in half.

Comment by robotact — July 12, 2012 @ 10:48 pm |

Could part 1 be proved inductively with respect to N?

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 10:22 pm |

It seems to me that if we could ask a series of questions to guarantee that x falls inside, say, [0, N/2], then we could reduce to a previous case, but once we find such a series of questions we more or less have solved the problem.

Comment by Jon — July 12, 2012 @ 10:24 pm |

My idea was that since the solution is obvious if N is inside [1,n], then we could simply prove the case n+1 and the rest would follow inductively.

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 10:27 pm |

It suffices to prove it for . See comment 12.

. See comment 12.

Comment by Kreiser — July 12, 2012 @ 10:44 pm |

Since there is a possibility that B would win the game simply by guessing, there is no “always win” for A.

Comment by S — July 12, 2012 @ 10:25 pm |

Good point, so it seems part 2 is somewhat harder than part 1. So it might be wise to completely focus on part 1 first.

Comment by Bob — July 12, 2012 @ 10:29 pm |

I agree – this relates back to comment 2

Comment by Alison — July 12, 2012 @ 10:31 pm |

Some observations. For the first part, proving for suffices. The first approach that comes to my mind is to induct on

suffices. The first approach that comes to my mind is to induct on  .

.

Comment by Marvis — July 12, 2012 @ 10:26 pm |

B can as well ask questions in “rounds” of k+1 questions. Then, each round is guaranteed to have at least 1 correct answer.

Comment by robotact — July 12, 2012 @ 10:27 pm |

While this is true, it is not very constructive. Player A can just answer about half truth and about half lies, making this strategy hard to implement.

Comment by Kreiser — July 12, 2012 @ 10:43 pm |

So for k=0 any version of binary search works. The next step should be to find the strategy for k=1, n=2. I first thought I have found the strategy, but it doen’t work.

Comment by Florian — July 12, 2012 @ 10:29 pm |

I am working on this case too. Here player A can never tell two lies in a row. Here is a little observation I have made. Let Q1, and Q2 be questions that player B can ask, and I will use the notation like:

Q’s: Q1 Q2 …

A’s: L T …

To denote that we asked Q1, then Q2 and we recieved a lie and a truth respectivly (of course, B doesnt know which).

Here is a cute little lemma:

Lemma: “If B asks Q1 Q2 Q1, then A must give the same answer for Q1 both times it is asked, or else tell the truth for Q2”

Proof: There are 5 possible ways A can answer. LTL, LTT, TLT, TTL, TTT. From here we see that if the answers to Q1 are different, then the only possibilities are LTT and TTL, in either case the answer to Q2 must be true. \box

Comment by Mihai Nica — July 12, 2012 @ 10:38 pm |

Two more little lemmas:

Lemma: “If Player B asks the same question twice in a row and the answer is the same both times, then it must have been true both times”

Proof: True since k=1

Lemma: “Let Q1,Q2 be questions. If player B asks the sequence of questions Q1 Q2 Q1 Q1 and gets answers A1 A2 A3 A4 (each Ai is either an L (lie) or a T(truth)). Then player A is forced to reveal one of the following pieces of information to player B. (i.e. player B will know which of them is true.)

i) A2 = T

ii) A3 = A4 = T

iii) A2 = A4”

Proof: By the last lemma for the sequence of questions Q1 Q2 Q1, player B knows that either A2=T or the answers to the first three questions are LTL, TLT, or TTT. In the former case we have i), in the latter case we know that the possible answers for all four questions is LTLT, TLTT, TLTL, TTTL, or TTTT. If A3=A4 then player B knows that they are both truths so we have ii). If not then the possibilies are LTLT, TLTL which gives iii).

Comment by Mihai Nica — July 12, 2012 @ 10:59 pm |

I think the second lemma can be used to make a binary seach by making Q1 = half the numbers, Q2= the other half of the numbers

Comment by Mihai Nica — July 12, 2012 @ 11:06 pm |

The second lemma solved the case k=1, see comment 15.

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 11:35 pm |

Here is an idea. Let’s first assume that is a power of 2. Say

is a power of 2. Say  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  . Think of numbers from

. Think of numbers from  to

to  as vertices of

as vertices of  -dimensional Boolean cube. Then let

-dimensional Boolean cube. Then let  be the

be the  -th coordinate of

-th coordinate of  . First,

. First,  asks if

asks if  (formally, B gives set

(formally, B gives set  ), then he asks if

), then he asks if  , and so on. Finally, he asks if

, and so on. Finally, he asks if  . He gets “yes” and “no” answers. In other words, he gets

. He gets “yes” and “no” answers. In other words, he gets  such that one of the statements “

such that one of the statements “ ” is true. Therefore, the first

” is true. Therefore, the first  bits of

bits of  cannot be equal

cannot be equal  . Thus B can exclude some values of

. Thus B can exclude some values of  , and essentially reduces

, and essentially reduces  . He proceeds until

. He proceeds until  . Then outputs the remaining numbers.

. Then outputs the remaining numbers.

Comment by Yury — July 12, 2012 @ 10:35 pm |

I thought about something similar, but it doesn’t seem to work since A could possibly answer the questions in a way so that no number gets excluded if is not a power of 2.

is not a power of 2.

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 10:42 pm |

If N is not a power of 2 but N > 2^{r+1}, B groups all numbers in 2^{r+1} non-empty clusters. The he labels each cluster, and all numbers in it, with a unique binary vector of length r+1. He then ask if the first bit of the label of x is 0; then if the second bit is 0, and so on. Finally, he finds a label L = (1 – b_1, …, 1 – b_{r+1}) such that x is not labeled with L. Now he can exclude all number with label B and iterate.

Comment by yurymakarychev — July 12, 2012 @ 10:50 pm |

Without loss of generality N can be assumed to be very large (at least for the first problem) because smaller Ns only make life easier for B. But the problem is that you can only exclude one number which A can choose by answering appropriately.

Comment by Florian — July 12, 2012 @ 11:03 pm |

You can assume that N = 2^k + 1, n = 2^k

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 10:51 pm |

In this case x will have at most k+1 binary digits, and the only case with k + 1 digits is (100…0), and all the combinations of k digits, how to exclude one number from there?

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 11:11 pm |

What we can do in this case is we keep asking if the first digit is 1, there are three possibilities,

k + 1 answers are YES, then the number is 10…0

k + 1 answers are NO, then we can exclude 10…0

Some answers are YES’s some NO’s, then we can choose the continent one, NO, and continue to ask for the other digits.

After we are done we can exclude a number whose first digit is 0 (because of the NO answer).

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 11:22 pm |

The method will handle the case when N \geq 2^{k+1}, in that case you can just take any subset of size 2^{k+1} and numerate from 1, …, 2^{k+1}, then exclude from that set, but what to do when the range gets less than 2^{k+1} ?

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 11:00 pm |

You need to ask at least k + 1 questions to make a conclusion.

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 11:01 pm |

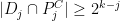

Reduction for part 1. (Assume all integers are from .)

.)

For part 1, it suffices to produce a winning strategy for . In other words, player

. In other words, player  can win for all

can win for all  iff he can win for

iff he can win for  .

.  is trivial.

is trivial.  is as follows:

is as follows:

Go by induction. Suppose and a winning strategy is known for all

and a winning strategy is known for all  . Partition

. Partition  into

into  nonempty sets

nonempty sets  . Then instead of asking "is it in

. Then instead of asking "is it in  ", he asks "is it in

", he asks "is it in  ? By using the winning strategy for

? By using the winning strategy for  , we can throw out one of the

, we can throw out one of the  and we now have a winning strategy by assumption.

and we now have a winning strategy by assumption.

Comment by Kreiser — July 12, 2012 @ 10:41 pm |

Let’s say we get answer for set

for set  , for

, for  , then if we take the complement of the answers then they can’t be true, but all of them being true corresponds an intersection of

, then if we take the complement of the answers then they can’t be true, but all of them being true corresponds an intersection of  ‘s or its complement, and in the case intersection is non-empty we can exclude the intersection points from the range for

‘s or its complement, and in the case intersection is non-empty we can exclude the intersection points from the range for  .

.

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 10:42 pm |

[…] Check out (and join in on) the discussion here. Share this:FacebookEmailTwitterLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in Event, Math, On the Web, Something Extra and tagged Game On!, IMO, International Math Olympiad, mini-polymath, Polymath by U. of Oklahoma Math Club. Bookmark the permalink. […]

Pingback by Minipolymath4 Project Now Open! | OU Math Club — July 12, 2012 @ 11:31 pm |

Case : By comment 12, it suffices to show this when

: By comment 12, it suffices to show this when  and

and  . Let Q1 and Q2 be the questions “is it in

. Let Q1 and Q2 be the questions “is it in  ” and “is it in

” and “is it in  “. Then after asking them in order Q1 Q2 Q1 Q1, we know by comment 10 either the thruth value of Q1 or Q2, in which case we are done, or using notation as in comment 10:

“. Then after asking them in order Q1 Q2 Q1 Q1, we know by comment 10 either the thruth value of Q1 or Q2, in which case we are done, or using notation as in comment 10:

1) If A2 and A4 were both “yes” or “no”, then .

. .

.

2) If one of A2 and A4 was “yes” and the other was “no”, then

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 11:32 pm |

This doesn’t quite seem correct. For instance, if x=1, then A can answer “yes” to all questions and only have to lie once.

Comment by Terence Tao — July 12, 2012 @ 11:38 pm |

But if A answers “yes” to all questions, B knows that x must be either 1 or 2, because A cannot lie twice in a row.

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 11:41 pm |

Well, ok, but A can instead answer “yes yes yes no” and this seems consistent with all three possibilities x=1, x=2, x=3, so B has been unable to eliminate anything.

Comment by Terence Tao — July 12, 2012 @ 11:52 pm |

Oh yes, true. My bad.

Comment by Olli — July 12, 2012 @ 11:58 pm |

We can assume N = 2^k + 1, n = 2^k.

It means that x has at most k + 1 binary digits (k+1 digits only for n = 2^k)

Then we can keep asking if b_1 is 1, there are two possibilities,

(a) k + 1 times we get the answer NO, then we exclude the number 10…0

(b) There is a YES answer. Then we stop asking about b_1 and ask b_2 = 1, b_3 = 1 … b_{k+1} = 1.

After we are done we can exclude the number for which all the last k + 1 asnwers would have been lies

whose first digit is 0 (because of the YES answer).

Comment by gagika — July 12, 2012 @ 11:43 pm |

Another way (which seems to solve the first question). We ask the sequence of question : “Does

: “Does  ?” in a row. That makes k+1 questions. Then we must have at least one of the digits right. In particular, let

?” in a row. That makes k+1 questions. Then we must have at least one of the digits right. In particular, let  be such that

be such that  if the answer to

if the answer to  is Yes, and

is Yes, and  if the answer to

if the answer to  is No. Then

is No. Then  . We have excluded a possibility, which by the reduction of comment 15 is enough.

. We have excluded a possibility, which by the reduction of comment 15 is enough.

Comment by Garf — July 13, 2012 @ 12:13 am |

Which number will you exclude in that case? (It might not be in the range)

Comment by gagika — July 13, 2012 @ 12:17 am |

When c_1 = 1, then the number might be out of the range.

Comment by gagika — July 13, 2012 @ 12:25 am |

I’m not sure I totally understand your argument, but your argument lead me towards the following:

Let be the subset of

be the subset of  with 0 as the

with 0 as the  digit in their binary expansion (note we’re leaving out one member). Let B ask

digit in their binary expansion (note we’re leaving out one member). Let B ask  in that order, and let

in that order, and let  be 0 if A says yes to

be 0 if A says yes to  and 1 else. Then let

and 1 else. Then let  be the number with binary expansion

be the number with binary expansion  where

where  . Now ask

. Now ask  in order.

in order.

Suppose A answers at least once that , and pick the first such instance of this. Then if

, and pick the first such instance of this. Then if  , A will have lied for the last

, A will have lied for the last  questions, ie

questions, ie  . So

. So  cannot be

cannot be  and we have the required win.

and we have the required win.

On the other hand, if A always says that for any

for any  , then if

, then if  was the one member we didn’t manipulate, A lied

was the one member we didn’t manipulate, A lied  times (all

times (all  questions). So if A says that

questions). So if A says that  for all

for all  , then the one member we didn’t manipulate is actually not

, then the one member we didn’t manipulate is actually not  , so we’ve discarded one member, and B wins.

, so we’ve discarded one member, and B wins.

Comment by Kreiser — July 13, 2012 @ 2:40 am |

I think you are missing one case:

“Suppose A answers at least once that , and pick the first such instance of this. Then if

, and pick the first such instance of this. Then if  , A will have lied for the last questions, ie . So cannot be and we have the required win.”

, A will have lied for the last questions, ie . So cannot be and we have the required win.”

What if A answers at least once that , and

, and  which mean that he didn’t lie.

which mean that he didn’t lie.

Comment by Gagik Amirkhanyan — July 13, 2012 @ 3:32 am |

Then $x\neq s_i$ and you guess everything except for $s_i$.

Comment by Kreiser — July 13, 2012 @ 5:57 am |

When you ask “if b_i = 1, …”, do you mean “if b_i is the only digit that has the value 1, … “?

Comment by abellong — July 13, 2012 @ 8:23 am |

Example for k=1 to see if I am following your logic.

Change indexing to be (0,N-1) to make indexing easier. Let N=3 and k=1 and n=2.

Ask about 2, if all No x is either 0 or 1 and done.

If we get a yes then ask about 1. If A answers yes then we have had two yes in a row and x is in (1,2) and we are done.

If we got a no then , A has answered 2 : yes, 1: no. The only possibilities compatible with this set of answers are, 2:true,1:false or 2: false,1: false. Therefore we can eliminate 1 and x is either 0 or 2.

It would be nice if someone writes out yhe same for N=5 and k=2.

Comment by Jeff — July 13, 2012 @ 2:40 pm |

[…] 4 has started. It is based on question 3 of the IMO. The research thread is here. There is a wiki here. Like this:LikeBe the first to like […]

Pingback by Mini-polymath 4 « Euclidean Ramsey Theory — July 13, 2012 @ 12:06 am |

Isn’t there something missing on the statement of the question? If I am B, then all my questions are of the form “is x \in { j }?”, where j = 1, 2, …, N, and I repeat each question k + 1 times. Since A cannot lie k+1 consecutive times, and x must be in { x }, the answer must be ‘yes’ after at most (k+1) x questions.

Comment by dd — July 13, 2012 @ 12:11 am |

Sorry! It is not as simple as I first thought because if there are mixed answers for a set, I may still not know which answer is correct. For instance, A can alternate between yes and no and no matter how many times I ask the same question I still can’t figure out which way is the truth.

Comment by dd — July 13, 2012 @ 12:15 am |

For part 2, we can again assume

N = n + 1, n = 1.99^k (the ceiling).

Comment by gagika — July 13, 2012 @ 12:38 am |

And A shouldn’t give B the possibility to exclude any number from the range [1, N]

Comment by gagika — July 13, 2012 @ 12:42 am |

For each number in the rang [1, N] at least one of every k + 1 answers in a row should be satisfied, so the number can be valid value for x.

A’s goal is to choose YES’s and NO’s in such a way

Comment by Gagik Amirkhanyan — July 13, 2012 @ 4:34 am |

Cant B just keep asking questions with singleton {y} for 2k consecutive times and then B can be sure of whether y=x??

Comment by Ronny — July 13, 2012 @ 1:35 am |

No. This has been discussed at least 2 other times- please read the thread before contributing. The standard counterexample is what happens if the answers are half yes and half no.

Comment by Kreiser — July 13, 2012 @ 2:00 am |

I think it goes along the following lines: suppose that you have built a sequence of k + 1 nested sets X_0 <= X_1 <= … <= X_k such that the answers of A indicate that none of the X_i contain the element x. Then we have confirmation that x is not an element of X_0. Indeed, if that was the case, then x must be in X_1, X_2, …, X_k and all the answers A gave were lies.

Try to build such a sequence where each nested set is at least half as large as the parent.

Comment by dd — July 13, 2012 @ 2:18 am |

[SPOILER: don’t read if you don’t want to see the solution]

To get the first part of the problem, proceed as follows. Suppose that we have determined that a set of t >= 0 values from [N] *cannot* be the element x. Then let us eliminate one more element provided that N – t >= 2^k + 1.

In this case, pick an arbitrary element y that you are still unsure could be x. Ask A repeatedly whether y is x. If the answer you get k + 1 times is NO, then it is the truth and you eliminated y as well. Otherwise, at some point A answers YES, which is equivalent to saying that there is a set X_k of size N – t – 1 >= 2^k which does not contain x. Now ask A about an arbitrary half of X_k if it contains x and this will determine a set X_{k – 1} \subset X_k with at least 2^{k – 1} elements that does contain x (according to A’s answer). Iterating yields a non-empty set X_0 for which you know x is not in X_0 (see the parent comment). You have thus eliminated |X_0| >= 1 elements from the set of candidates for x.

Doing this until N – t = 2^k yields the set with the desired property.

Comment by dd — July 13, 2012 @ 2:36 am |

I think Comment 16 (and also Comment 21, which seems to be basically the same argument) has resolved the first part of the problem. Looks like the second part is still almost untouched, though (except for the short observation in Comment 19)…

Comment by Terence Tao — July 13, 2012 @ 4:08 am |

You can try to solve both parts for the “truth”, which is harder but doable (and was the original problem). I won’t (yet) mention the optimal so as to not risk giving any hints for part (b)

so as to not risk giving any hints for part (b)

Comment by Ralph Furmaniak — July 13, 2012 @ 5:45 am |

What do you mean by truth? In the above we have solved for the set containing X.

Comment by jbergmanster — July 13, 2012 @ 2:45 pm |

I think Ralph is using “the truth” to refer to the true threshold for n (i.e. the least n for which B has a winning strategy, or equivalently the first n for which A no longer has a counterstrategy). The problem as stated places this threshold below or equal 2^n, and above or equal (1.99)^n for sufficiently large n, but is presumably somewhere in between. (e.g. it might be something like , which sometimes shows up as a threshold in some other extremal combinatorics problems.)

, which sometimes shows up as a threshold in some other extremal combinatorics problems.)

Comment by Terence Tao — July 13, 2012 @ 4:07 pm |

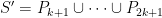

Some ideas for the second part: ? In that case, (b) follows from the fact that there exists an integer

? In that case, (b) follows from the fact that there exists an integer  for sufficiently large

for sufficiently large  .

. ,

,  , B does not have a winning strategy.

, B does not have a winning strategy.

1) Could it work for any

2) If above is true, we would only need to show that for

Comment by Olli — July 13, 2012 @ 7:12 am |

Possibly some variant of greedy algorithm would work?

Comment by Olli — July 13, 2012 @ 7:33 am |

So should k=6 work with ceil(1.99^6) = 63 and N=64. Or do we need a larger gap of order k?

Comment by jbergmanster — July 13, 2012 @ 3:01 pm |

I guess we can abate the rules of game namely that instead of A not being able to lie for k+1 moves in a row, he is able to lie for k+1 moves in a row, but he will lose at the end of the game if he ever does that.

Looks like one possible approach might be probabilistic deduction. Something like A’s strategy is random and B’s strategy is deterministic.

Can we say that it is enough that B asks only finitely many questions by some reasoning (something similar than some problems needs to be checked only in finitely many cases by compactness argument)?

Comment by Jaakko — July 13, 2012 @ 8:51 am |

[…] Edit: As of Friday morning (7/13/2012), the problem still has not been completely solved, so there’s time to chime in on the discussion thread! […]

Pingback by Polymath project: social problem-solving | Civil Statistician — July 13, 2012 @ 1:21 pm |

Some observations:

we can again assume

N = n + 1, n = 1.99^k (the ceiling).

The strategy for A will be for each value of x in the range [1, N] to have at least 1 correct answer in each k + 1 consecutive queries.

Each time A picks to answer he can choose YES or NO in such a way that at least for half of the numbers in {1, 2, … N} it will be true.

Comment by Anonymous — July 13, 2012 @ 3:25 pm |

It would be enough to show that there is a set S of size where

where  such that for all choices of

such that for all choices of  in

in  , A could give the same answers to all of B's questions while still maintaining the required conditions. In this case it would seem that B cannot be done if n = M – 1.

, A could give the same answers to all of B's questions while still maintaining the required conditions. In this case it would seem that B cannot be done if n = M – 1.

Comment by Nirman — July 13, 2012 @ 3:26 pm |

To approach part 2, I guess the easiest idea is to try to give a strategy for A. From part 1, we learned that we can as well start with a set of size N = n+1, and B tries to exclude some element i in {1,…,n+1} as being x.

Thus, B will specify sets S_1, S_2, … and A needs to answer in turn. At any point in time, A wants that *each* value i in {1,…,n+1} is still a possibility for x. Thus, suppose we answered the previous questions S_1,…,S_k somehow, and we are given S_{k+1} which we want to answer. We now build a 0/1-matrix, with columns 1,…,k and rows 1,…,n+1. For each (i,j) we put a 1 in an entry in case we answered question j (about S_j) such that x = i is a possibility.

Thus, this looks now like the following game: B provides a subset of the columns S. A then add a column to the matrix, where either exactly the entries in S have a 1, or exactly the entries in {1,..,n+1} \ S have a 1. If at any point in time some row has only zeros in the last k+1 columns, A loses.

We can now try to give strategies which can handle as many rows as possible (even if it is way less than 2^k).

Comment by Anonymous — July 13, 2012 @ 3:29 pm |

This is a very vague idea but part b) reminds me of the sort of problems I encountered in an Information Theory class a long while ago. It was especially common to prove inequalities in the limit like that in part b). So perhaps the problem could be phrased in Information Theoretic language? e.g. “The answers provided by A can only reduce the entropy so much”.

But as I hardly remember the details of information theory I may be way off base…

Comment by letmeitellyou — July 13, 2012 @ 3:57 pm |

Since the ratio of 1.99^n to 2^n becomes arbitrarily small the following method could possibly work. Start with any example that doesn’t work and find a way to double it one more lie any number of times. Then eventually it will be between 1.99^n and 2^n and it will be the desired counterexample. This has the virtue of allowing us to look at small counterexamples first. Do we have a list of counterexamples when the number is less than 2*n and A wins? Perhaps that would be useful. I would be interested in what information A can hide and how.

Comment by kristalcantwell — July 13, 2012 @ 5:29 pm |

So let’s take a concrete factor. Suppose you face half the number of questions which guarantee success – is there a strategy that works? The number 2 seems to be intimately connected to the problem, which suggests that half might be a good proportion to try.

Comment by Mark Bennet — July 13, 2012 @ 6:38 pm |

In part (b), we need to develop a strategy for 1st player. If I were him, I would take X=n+1, and do not choose x at all. Then, I would try to answer in such a way, that after all n+1 possible choices of x there is no k+1 succesive lies. If this can be done, after any n-element guess of 2nd player, I can claim that x is the n+1-st element. This is a beat cheting, but it works :)

Comment by Anonymous — July 13, 2012 @ 5:36 pm |

I mean N=n+1

Comment by Anonymous — July 13, 2012 @ 5:38 pm |

Now, let a(i), i=1,…,n+1 be a number of succesive lies up to now, if x=i. Then, at every step, I have vector (a(1),a(2),…,a(n+1)). For example, with n+1=4 I start with vector (0,0,0,0). After question about set {1,2,3}, I can say “yes” to get vector (0,0,0,1) or “no” to get (1,1,1,0). Obviously, better to say “yes”. In this case, if next question is about set {1,4}, I can say “yes” to get (0,1,1,0) or “no” to get (1,0,0,2). In any case I can round some numbers to 0 but increase other numbers by 1. I loose if I get k+1 somewhere.

Comment by Bogdan — July 13, 2012 @ 5:49 pm |

In case there are two entries which contain k, we also already lost, because we can’t guarantee neither of them goes to k+1. Analogously, if there are 4 entries which contain k-1, or if there are 8 entries containing k-2.

Comment by Anonymous — July 13, 2012 @ 6:38 pm |

We can think of the game in the following way.

B asks questions about the sets

S_1, S_2, … , S_k,…

And A should make a choice (by answering YES or NO) of S_i or its complement in each time and we will get

D_1, D_2, … D_k, …

where D_i is either S_i or the complement of S_i (A has the option to choose)

A wants to do in a way that for each m, all the numbers from the range [1, N] appear at least once in the sequence

D_m, D_{m+1}, … D_{m+k}

Comment by Gagik Amirkhanyan — July 13, 2012 @ 7:23 pm |

We use a greedy approach to choose D_i

We choose

D_1 = S_1 if | S_1 | > N/2 t, otherwise D_1 = Compliment(S_1).

To pick D_2 we can see whether S_2 or complement (S_2) covers at least 1/2 portion of [1, N] \ D_1

We pick D_{i+1} such that it covers at least 1/2 portion of D\(D_1 u D_2 … u D_i}.

We can claim that in at least p = log_2 N steps D_1 u D_2 … u D_p = [1, N]

Where p = k log_2 (1.99).

It means that for each of the numbers [1, N] we A gave at least one correct answer in the first p steps.

Because p > k / 2, it will not imply part b), probably some modifications are needed.

Comment by Gagik Amirkhanyan — July 13, 2012 @ 8:04 pm |

Since this is a cooperative effort, let me blurt out some weaker result for part 2 which may be refined to give the desired result. there is no winning strategy for B.

there is no winning strategy for B.

Suppose that we just want to prove that for

We let N = n + 1.

Before describing A's strategy let us look at what B must do. After a finite number of rounds, B provides a set of n elements which he claims must contain x. In other words, B is stating that precisely one element y from [1, N] should not be x. What we have to show is that all of A's answer are compatible with y being equal to x. More precisely, we have to show that for x = y, the sequence of answers do not contain any k+1 consecutive lies.

A's answers are encoded as a sequence of sets such that each answer is of the form x does not belong to

such that each answer is of the form x does not belong to  . If the set given by B on the ith round is

. If the set given by B on the ith round is  then the set

then the set  is either

is either  or its complement. A's choice for

or its complement. A's choice for  is arbitrary (say

is arbitrary (say  ). For

). For  , pick

, pick  such that |intersection of S_0, S_1, …, S_i| <= |intersection of S_0, …, S_{i – 1}| / 2. In particular, the intersection of

such that |intersection of S_0, S_1, …, S_i| <= |intersection of S_0, …, S_{i – 1}| / 2. In particular, the intersection of  is empty. After this, A starts fresh with the

is empty. After this, A starts fresh with the  and repeats the same process again.

and repeats the same process again.

Now for any choice of y that B selects, all the answers of A are compatible, since for any k + 1 consecutive sets in the sequence there must be a subsequence of k/2 + 1 terms

there must be a subsequence of k/2 + 1 terms  such that their common intersection is empty. In particular, y cannot be in all of the sets

such that their common intersection is empty. In particular, y cannot be in all of the sets  , so one of those answers was truthful.

, so one of those answers was truthful.

Comment by dd — July 13, 2012 @ 7:39 pm |

The game can be re-formulated in an equivalent one: The player chooses an element

chooses an element  from the set

from the set  (with

(with  ) and the player

) and the player  asks the sequence of questions. The

asks the sequence of questions. The  -th question consists of

-th question consists of  choosing a set

choosing a set  and player

and player  selecting a set

selecting a set  . For every

. For every  the following relation holds:

the following relation holds:  The player

The player  wins if after a finite number of steps he can choose a set

wins if after a finite number of steps he can choose a set  with

with  such that

such that

a) It suffices to prove that if then the player

then the player  can determine a set

can determine a set  with

with  such that

such that  . Assume that

. Assume that  . In the first move

. In the first move  selects any set

selects any set  such that

such that  and

and  . After receiving the set

. After receiving the set  from

from  ,

,  makes the second move. The player

makes the second move. The player  selects a set

selects a set  such that

such that  and

and  . The player

. The player  continues this way: in the move

continues this way: in the move  he/she chooses a set

he/she chooses a set  such that

such that  and

and  . In this way the player

. In this way the player  has obtained the sets

has obtained the sets  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  such that

such that  . Then

. Then  chooses the set

chooses the set  to be a singleton containing any element of

to be a singleton containing any element of  . There are two cases now:

. There are two cases now:  The player

The player  selects

selects  . Then

. Then  can take

can take  and the statement is proved.

and the statement is proved.  The player

The player  selects

selects  . Now the player

. Now the player  repeats the previous procedure on the set

repeats the previous procedure on the set  to obtain the sequence of sets

to obtain the sequence of sets  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . The following inequality holds:

. The following inequality holds:

However, now we have

and we may take .

.

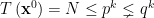

(b) Let and

and  be two positive integers such that

be two positive integers such that  . Let us choose

. Let us choose  such that

such that

We will prove that for every if

if  then there is a strategy for the player

then there is a strategy for the player  to select sets

to select sets  ,

,  ,

,  (based on sets

(based on sets  ,

,  ,

,  provided by

provided by  ) such that for each

) such that for each  the following relation holds:

the following relation holds:

Assuming that , the player

, the player  will maintain the following sequence of

will maintain the following sequence of  -tuples:

-tuples:  . Initially we set

. Initially we set  . After the set

. After the set  is selected then we define

is selected then we define  based on

based on  as follows:

as follows:

The player can keep

can keep  from winning if

from winning if  for each pair

for each pair  . For a sequence

. For a sequence  , let us define

, let us define  . It suffices for player

. It suffices for player  to make sure that

to make sure that  for each

for each  . Notice that

. Notice that  . We will now prove that given

. We will now prove that given  such that

such that  , and a set

, and a set  the player

the player  can choose

can choose  such that

such that  . Let

. Let  be the sequence that would be obtained if

be the sequence that would be obtained if  , and let

, and let  be the sequence that would be obtained if

be the sequence that would be obtained if  . Then we have

. Then we have

Summing up the previous two equalities gives:

because of our choice of .

.

Comment by akash chayan — July 13, 2012 @ 7:53 pm |

I think it’s correct solution, just in the definition of x_i^{j+1} should be P_i instead of S. [Corrected, -T.]

Comment by Gagik Amirkhanyan — July 13, 2012 @ 8:14 pm |

Dear all,

As this thread is becoming quite full, I am opening a fresh thread at https://polymathprojects.org/2012/07/13/minipolymath4-project-second-research-thread/ to refocus the discussion. I’ll leave this thread open for responses to existing comments here, but if you could put all new comments in the new thread, that would be great. (Now would also be a good time to resummarise some of the observations made in this thread onto the fresh thread, to make it easier to catch up.)

Comment by Terence Tao — July 13, 2012 @ 7:56 pm |

[…] the previous research thread is getting quite lengthy (and is mostly full of attacks on the first part of the problem, which is […]

Pingback by Minipolymath4 project, second research thread « The polymath blog — July 13, 2012 @ 8:04 pm |

[…] (Rubinstein would say that this is true of most real-life applications of game theory as well.) Try your hand, or look at the comments, which surely have spoilers by now as it has been up for about a day: […]

Pingback by Game Theory at the Polymath Project « The Leisure of the Theory Class — July 13, 2012 @ 8:47 pm |

Reblogged this on Wikipedia Afficianado and commented:

IMO is the Mecca of young mathematicians battling out in this divine field of which I am in oblivion of until now. Whenever I try and study mathematics it is with a notion of solving a problem and that problem is hard enough for veterans to try but what I have come to know from those who do “Research” is that they don’t do it to solve the problem but to firstly understand it well and secondly to find why is that problem tough than what it seems to be. Terence Tao as you all know is a known child prodigy and inculcated abilities to solve problems involving numbers at a very young age. He id the youngest even to have received a fields medal. This Re-Blogged post concerns a question which appeared in this year’s IMO (International Mathematical Olympiad in case you are not familiar with what it is) and a good thread to discuss what comes to your mind while approaching it.

Comment by prateekchandrajha — July 30, 2012 @ 10:58 pm |

1) for the case of k consecutive responses one of which is true:

we supoose k = 0, so all answers are true, so we can know the exact number x, so n = 1 ≥ 2 ^ 0

I now propose a case that will help me in my demonstration:

2) For k+2 consecutive responses which one is true and one is false :

we assume that k = 0, so two consecutive responses contiennt true and the other false, so thanks to our given 1 ≤ x ≤ N, making this series of questions:

* X = 0?

* 1 ≤ x ≤ N?

* X = 1?

* 1 ≤ x ≤ N?

.

.

.

I will know the exact number x, so in this case n = 1 ≥ 2^0

*** Now assume that for k+1 consecutive responses which one is true n must be n ≥ 2 ^ k

one must demonstrate that responses to k+2 n in this case must be n ≥ 2 ^ (k +1)

and *** k+2 consecutive responses which one is true and one is false n must be n ≥ 2 ^ k

we must show that for k+3 consecutive responses in this case n must be n ≥ 2 ^ (k +1)

1 *) where k+2 consecutive responses which one is true can be divided into two cases:

— K 2 answers are true then n ≥ 1

— K 2 answers contiennet true and another false must therefore n ≥ 2^k

so it is sufficient to write n ≥ 2^(k+1)

2 *) where k+3 consecutive responses which one is true and the other must be false can be divided into two cases:

— K+2 answers are wrong and one seulle is true: in this case the placement of the true answer is the same after each k+2 answers, so to see her placement just ask the same question k+2 times and the correct answer will be different among the answers … and how we can know the exact number x, so n ≥ 1

— K+3 answers contain at least two answers true and one false: this case is a special case of the general case (k+2 consecutive responses of which is true), so n ≥ 2 ^ (k +1)

It’s finished

Comment by Anonymous — August 22, 2012 @ 3:27 pm |